Aluminum: The Hidden Carbon Cost No One Is Talking About

/Aluminum is a pillar of sustainable infrastructure and green technologies, appearing in everything from the batteries in our phones to the electric cars we drive. However, its production cannot be truly called “green” until its full climate impact is acknowledged and accounted for. Maria Guillamont, a Juris Doctor candidate at Lewis & Clark Law School and Legal Intern at SDSG, has been researching the overlooked environmental impact of aluminum – and why it matters now more than ever.

By Maria Guillamont

Mining equipment at the Comalco bauxite mine, Weipa, Australia (credit: Urbain J. Kinet / Berkeley Geography); certified pisolitic bauxite from Arkansas, USA (credit: James St. John via Flickr, CC BY 2.0); aluminum foil (credit: James St. John via Flickr, CC BY 2.0) (Montage: SDSG)

Why aluminum is everywhere

Chances are, you’ve interacted with aluminum countless times today. Whether you checked your smartphone, drove to work, opened a can of soda, or even flipped a light switch, aluminum played a silent but vital role.

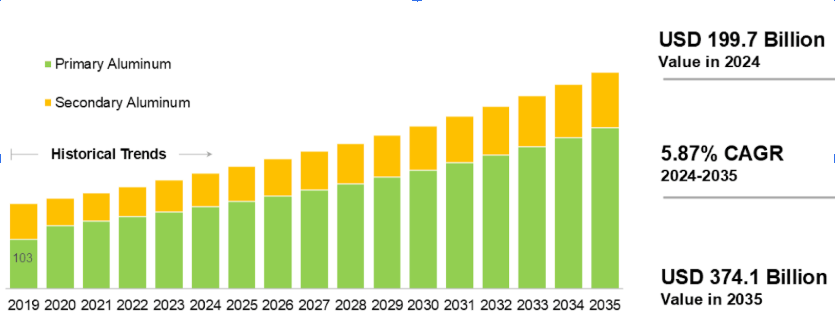

This malleable and ductile metal is indispensable across various industries, making it one of the most-used components of our modern world. It sits at the core of battery enclosures, motor housings, heat exchangers, and electrical systems. Because of its many uses, this metal is central to the energy transition. As the world scales up electric vehicle production and renewable energy infrastructure, aluminum demand is set to grow substantially – with projections suggesting an increase of 40 to 50% by 2050.

Aluminum market growth projection until 2035 (source: https://www.rootsanalysis.com/)

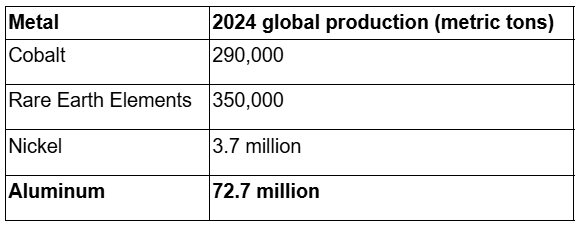

The scale of this industry is already massive today, dwarfing the production of other ‘transition metals’:

Source: Maria Guillamont

Aluminum production is more than ten times the volume of all these other materials combined. Because the industry is so vast, it is imperative that its environmental footprint is known and accurately reported.

Where the damage begins: bauxite and rainforests

Aluminum does not exist in nature in its pure form; it is refined from bauxite, a reddish ore found mostly in tropical rainforests. Around two thirds of global bauxite reserves are located in Guinea, Australia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Brazil, specifically in regions that house some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems and large tropical forests. This overlap means that bauxite mining often has serious environmental consequences.

Unlike many minerals that are found deep underground, bauxite primarily occurs in shallow, widespread deposits. Extracting it requires open-pit mining, which involves clearing large tracts of land or forest, stripping away topsoil, and disturbing underlying rock layers. This results in large-scale deforestation, habitat loss, and the disturbance of carbon-sequestering soils. Some of the environmental and social issues around aluminum production have previously been explored by SDSG.

Image Source: https://www.hikewest.org.au

The scale of projected land disturbance in regions of high conservation value is staggering:

In Guinea, bauxite mining is projected to destroy over 445,000 hectares (or 1.1 million acres) of natural habitat within the next two decades;

In Australia, proposals could disturb up to 100,000 hectares of land in the Jarrah forest, a biodiversity hotspot with endangered endemic species;

In Indonesia and in Brazil, similar projections show several hundred thousand hectares at risk in each country due to active sites and mining licenses granted.

The carbon cost and the accounting gap

Here is the crux of the issue: rainforests are our most powerful terrestrial carbon sinks. The Amazon alone used to absorb about 5% of global CO₂ emissions each year, but its ability to sequester carbon is degrading due to climate change and deforestation. When these forests are cleared for bauxite extraction, we don’t just lose trees: we release the carbon stored both above- and below-ground into the atmosphere, contributing significantly to climate change. Not only that, but we also diminish nature’s ability to absorb future emissions.

As part of my research at SDSG, I reviewed 20 academic and aluminum industry articles related to Greenhouse Gas emissions in the bauxite/aluminum sector. The review reveals a troubling trend: this loss of carbon sequestration capacity is almost entirely absent from major industry reports, life cycle assessments, and emissions accounting frameworks.

Despite the mounting evidence, deforestation-related carbon loss is not meaningfully included in emissions calculations by industry bodies like the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative (ASI) or the International Aluminum Institute (IAI).

For instance, ASI’s 1.5°C roadmap focuses on decarbonizing electricity inputs and improving smelting efficiency. However, it provides only vague assurances that emissions from land-use change will be integrated into the roadmap in the future, and fails to quantify the actual climate cost of forest destruction.

This omission is critical. According to Global Forest Watch, forests in Guinea currently remove over 43 MtCO₂e annually. Studies looking at the average of forests’ carbon storage see that approximately 44% of all carbon stock is stored in soil, up to one meter depth. Mining for Bauxite disturbs not just trees, but also this rich underground carbon reserve.

Forest loss driven by the growing aluminum demand would therefore undermine global climate goals, yet the aluminum industry provides an incomplete picture of its carbon footprint in its emissions reports. Without this information, we have a huge gap in our understanding of the carbon cost of bauxite mining.

Redefining transparency

This gap in environmental accounting must be closed urgently; all emissions, especially those from forest and soil carbon loss, must be transparently reported and mitigated. Without this, industry reduction targets are fundamentally incomplete.

Organizations like ASI claim to promote “full life cycle assessments” and transparent reporting. Yet, by failing to account for forest carbon loss, their standards fall short of their own transparency goals. We cannot build a green future on a foundation of ‘hidden’ emissions.

The Path Forward

It is imperative that exhaustive reporting of carbon emissions from land use changes be present across environmental assessments and carbon accounting of the Aluminum industry. As such, SDSG is working to develop a research and action initiative to quantify carbon stocks in soils and vegetation across bauxite-rich regions through a global literature review, spatial analysis of existing and planned mining in forested areas, and targeted soil carbon data collection. In parallel, SDSG intends to work with partners in bauxite-rich countries to assess legal and policy frameworks governing land use, restoration, and public participation in mining decisions. Our objective is to produce evidence-based recommendations to inform regulatory reforms to account for this gap in Aluminum environmental assessments, as well as strengthen standards to minimize carbon loss and provide practical guidance to support carbon soil conservation and landscape restoration.