Mining Legacy, Living Landscape: A Field Study of Uranium on the Navajo Nation

/In the Southwestern U.S., uranium mining powered national ambitions, transformed landscapes, and left behind challenges that persist decades later. Drawing on observations from a recent field course in the Four Corners region, Luke Danielson, President of Sustainable Development Strategies Group, explores what the Navajo Nation’s experience reveals about the legacies of mining, reclamation work, and the importance of learning directly from the places and people affected.

By Luke Danielson

Participants visiting an abandoned uranium mine near Cove, Arizona (Photo L. Danielson).

In June last year, the Executive Director of Western Alliance of Reclamation Management (WARM), Dominique Naccarato, and I were among the leaders of a week-long field course to study reclamation needs and current actions at mine sites across the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona.

The course was organized by WARM and the Society of Economic Geologists (SEG), and gathered students from Western Colorado University, Colorado School of Mines, Colorado State University, the University of Arizona, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and more.

While the course was based primarily at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, we visited many sites, encountering a wide range of mining landscapes and histories – from former silver mines in the high San Juans in Colorado to copper mining districts in Utah. This post focuses specifically on the legacy of mining on the Indigenous Navajo Nation. While coal, gold, copper and other minerals have all played important roles, the most frequent and visible impacts are associated with uranium mining.

a newcomer in the mining world

Humans have been mining for far longer than they have domesticated animals or grown crops. Early mining likely began 50,000 years ago, initially focused on a very limited number of materials. Over time, advances in technologies both required and enabled the production of a growing list of materials.

A relative newcomer to this list is uranium. Prior to World War II, small amounts were produced as a byproduct of vanadium or other ores. One notable usage example from this period is FiestaWare, a dinnerware company created in 1936, which used uranium glazes to produce plates with a bright orange-red hue.

A Fiesta red saucer (credit: Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity)

Mining uranium as a primary objective, however, awaited the development of nuclear weapons at Los Alamos, New Mexico during World War II. The first of these weapons was detonated in New Mexico, at the Trinity site in the Jornada del Muerto, marking a turning point not only in warfare, but in global demand for uranium. My stepfather, Frank Oppenheimer, played a role in the Manhattan Project, and was present at the Trinity Test, which he helped organize.

from boom…

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the end of World War II, the world entered an arms race that drove an urgent demand for uranium. There was also the potential that nuclear technology could be used to power ships, generate electricity, and reshape modern life. The United States (U.S.) did not want to fall behind.

The federal government was concerned that supplies of uranium might prove too limited, or worse, that our nation’s adversaries might have more of it than we did. It was a (self-fabricated) crisis atmosphere, not too different from what we are seeing today with critical minerals. The Atomic Energy Commission and other agencies established a host of incentives to promote uranium prospecting and production. These measures fueled what became known as the 1950s “uranium boom” (which gave its name to a 1956 Hollywood movie).

Large uranium deposits were identified, much of them in New Mexico. The mining happened rapidly and often haphazardly, leaving behind a massive and very troubling social and environmental legacy. Some of this is described in Judy Pasternak’s book, Yellow Dirt: a Poisoned Land and the Betrayal of the Navajos. Miners dug uranium from small, poorly ventilated tunnels with dangerous radiation levels. Mill waste was inadequately contained and leached into groundwater. The resulting impacts mean there will be work for generations of reclamation specialists.

…to bust

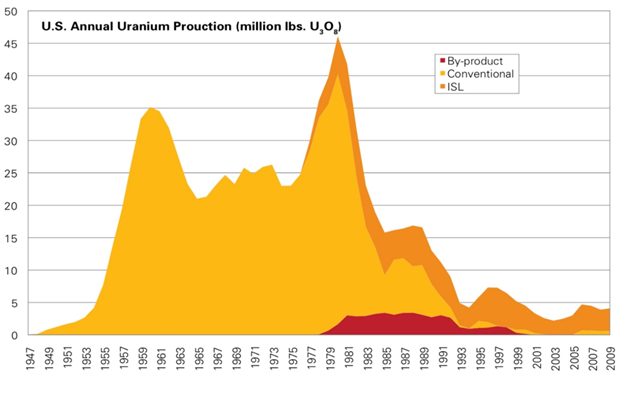

Ironically, the success of these incentives led to overproduction. By the 1960s, government stockpiles had grown too large, subsidies were removed, and the industry moved abruptly from boom to bust.

This is a lesson in the minerals industries. Government subsidies drove the silver boom of the 1880s and 1890s, followed by a bust when the subsidies ended. The U.S. may be repeating the same mistakes in the current drive to find and develop critical minerals and rare earths.

Annual uranium production in the United States, 1947-2009. Adapted from Fettus and McKinzie, Nuclear Fuel’s Dirty Beginnings, NRDC (March 2012).

Because little attention was given to closure planning, the collapse of uranium mining left a legacy of uncontrolled environmental impacts on the landscape. These included about three dozen uranium mill tailings sites, which have cost government billions of dollars to stabilize and remediate under the Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act. There is a Radiation Exposure Compensation Act which provides compensation to former uranium miners and other uranium workers. RECA was expanded in 2025 to cover more workers, survivors, and specific diseases like kidney cancer and disease.

Today, there are still more than 500 federally recognized abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation alone, and more than 10,000 across the western United States. Reclaiming these sites will take decades.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DoE)’s Defense-Related Uranium Mines (DRUM) program works in partnership with federal land management agencies, state abandoned mine lands programs, and tribal governments to verify and validate the condition of uranium mines that provided ore to the Atomic Energy Commission for defense-related activities between 1947 and 1970.

Remediation up close

During the field course, we met with teams from the DoE, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Navajo Abandoned Mine Lands Department, mining company Freeport-McMoRan, the Southwest Research and Information Center, and others engaged in this work.

At Shiprock, New Mexico, our group was hosted by a DoE team led by Site Manager Joni Tallbull. Shiprock is home to a major repository for mill tailings from the former Shiprock Uranium Mill, one of several such sites in the region.

Mill tailings disposal site at Shiprock, New Mexico (Photo L. Danielson, SDSG).

Originally, these tailings were placed on permeable soils in the alluvium along the San Juan River, allowing contaminants to infiltrate groundwater. Protecting groundwater is now a major focus of reclamation efforts.

The uranium milled here came from dozens of small mines, often located around Cove, Arizona. Several of these are now being remediated by Freeport-McMoRan, which did not create these legacies but is cleaning up many of them.

Abandoned uranium mine near Cove, Arizona (Photo L. Danielson, SDSG).

Our group visited several other sites managed by Jennifer Laggan, Manager for Remediation Projects at Freeport, and the team she leads.

Visit to Abandoned Uranium Mine (Photo Luke Danielson, SDSG).

The course also included some hands-on work in sampling and monitoring, including measuring radiation levels, to center policy discussions in the realities of site conditions and remediation.

Church Rock’s enduring impacts

Participants were then hosted by members of the Church Rock community in New Mexico, located next to the largest uranium mine on the Navajo Nation. Although the mine is now closed, it has not yet been fully reclaimed. Several nearby sites still require significant remediation, and concerns over ongoing radiation exposure remain considerable.

As early as 1979, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission noted that “uranium mining and milling are currently the most significant sources of radiation exposure to the public from the entire uranium fuel cycle, far surpassing other stages of the fuel cycle, such as nuclear power reactors or high level radioactive waste disposal”.

That very same year, Church Rock became the site of a uranium mill tailings spill, the largest release of radioactive materials in U.S. history. In a 2025 blog note, Dr Chanese A. Forté of the Union of Concerned Scientists describes the release of “1,000 tons of tailings and 93 million gallons of acidic wastewater into the Rio Puerco, traveling about 80 miles downstream to eastern Arizona. People who waded unknowingly into the river immediately after the spill suffered acid burns on their feet and legs, and an unknown number of livestock (...) were also lost in the river”.

Kenyon Larsen of EPA with students at Church Rock, New Mexico (Photo L. Danielson, SDSG).

Conversations with Church Rock community members were among the most powerful moments of the field course. Participants heard firsthand accounts of family members who developed lung cancer and other diseases after working in the uranium industry, of areas perceived as no longer safe for living, and of impacts on agricultural livelihoods.

Billboards along local highways informing people of their rights to file claims were another sobering reminder that yesterday’s choices have long lasting consequences. Some of the issues the Navajo faced are further documented in a book The Navajo People and Uranium Mining.

Meeting with community members and experts at Church Rock (Photo L. Danielson, SDSG).

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) is a federal program that provides one-time compensation to eligible former uranium miners, millers, and ore transporters who develop certain radiation-related illnesses. While originally limited to workers active between 1942 and 1971, recent legislation has extended its coverage to miners through to 1990 and broadened the list of eligible diseases.

Returning to the Navajo Nation

This field course highlighted the importance of learning directly from practitioners and communities about the legacies of mining and milling uranium. We are currently planning an expanded and more advanced version of this field course in 2026, anticipated to include coal, copper and other mining sites on the Navajo Nation and elsewhere in addition to uranium. We also hope this future course will involve collaboration with Navajo Technical University. If you are interested in joining a future tour, further details will soon be available at https://www.segweb.org/.

This field course benefitted enormously from the generosity, expertise and time of many individuals and organizations. We would particularly like to thank Cory Dayish and Benjamin Deans of the Division of Natural Resources of the Navajo Nation for their guidance and support.